Physiological/Biological Psychology explores how our brain and biology influence our... Show more

Sign up to see the contentIt's free!

Access to all documents

Improve your grades

Join milions of students

Knowunity AI

Subjects

Triangle Congruence and Similarity Theorems

Triangle Properties and Classification

Linear Equations and Graphs

Geometric Angle Relationships

Trigonometric Functions and Identities

Equation Solving Techniques

Circle Geometry Fundamentals

Division Operations and Methods

Basic Differentiation Rules

Exponent and Logarithm Properties

Show all topics

Human Organ Systems

Reproductive Cell Cycles

Biological Sciences Subdisciplines

Cellular Energy Metabolism

Autotrophic Energy Processes

Inheritance Patterns and Principles

Biomolecular Structure and Organization

Cell Cycle and Division Mechanics

Cellular Organization and Development

Biological Structural Organization

Show all topics

Chemical Sciences and Applications

Atomic Structure and Composition

Molecular Electron Structure Representation

Atomic Electron Behavior

Matter Properties and Water

Mole Concept and Calculations

Gas Laws and Behavior

Periodic Table Organization

Chemical Thermodynamics Fundamentals

Chemical Bond Types and Properties

Show all topics

European Renaissance and Enlightenment

European Cultural Movements 800-1920

American Revolution Era 1763-1797

American Civil War 1861-1865

Global Imperial Systems

Mongol and Chinese Dynasties

U.S. Presidents and World Leaders

Historical Sources and Documentation

World Wars Era and Impact

World Religious Systems

Show all topics

Classic and Contemporary Novels

Literary Character Analysis

Rhetorical Theory and Practice

Classic Literary Narratives

Reading Analysis and Interpretation

Narrative Structure and Techniques

English Language Components

Influential English-Language Authors

Basic Sentence Structure

Narrative Voice and Perspective

Show all topics

98

•

Feb 8, 2026

•

eljiy

@eljiy_7gkrr

Physiological/Biological Psychology explores how our brain and biology influence our... Show more

Ever wonder what happens when your brain can't form new memories? The case of Jimmie G. demonstrates this heartbreaking reality. At 49 years old, Jimmie couldn't remember anything that happened since his early 20s due to Korsakoff Syndrome. Despite normal intelligence, he lived frozen in time—believing he was 19 and unable to form new memories, even forgetting conversations moments after having them.

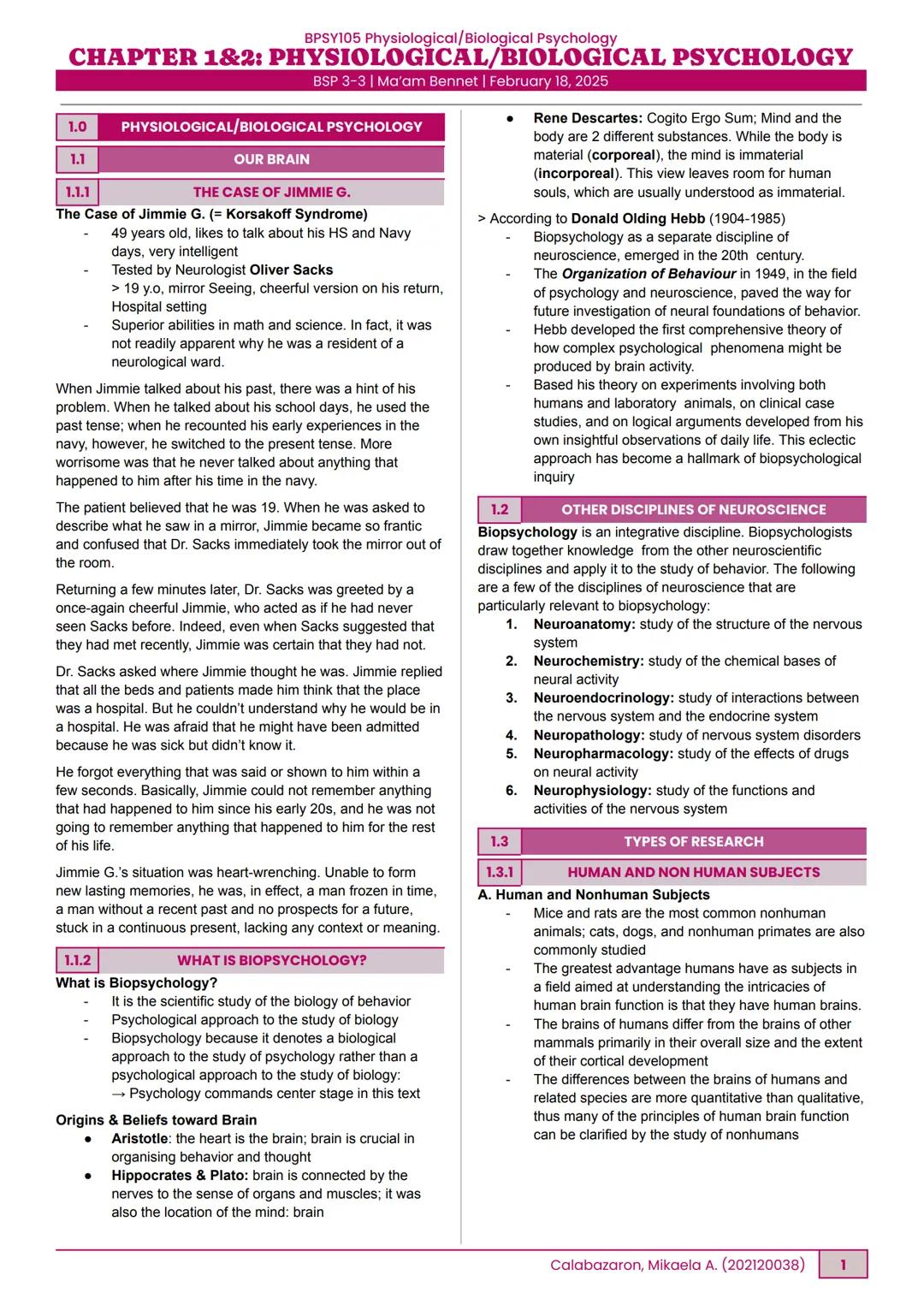

Biopsychology is the scientific study of the biology of behavior. Unlike early thinkers like Aristotle (who believed the heart was central to thought), modern biopsychology follows the tradition of Hippocrates and Plato, who correctly identified the brain as the command center for behavior and thought. A key historical figure, Donald Olding Hebb, established biopsychology as a separate discipline in the 20th century with his 1949 work "The Organization of Behaviour."

Biopsychology integrates knowledge from multiple neuroscience disciplines including:

Insight Box: Biopsychologists use an "eclectic approach" combining experiments with humans and lab animals, clinical case studies, and logical arguments based on observations of daily life—a signature characteristic of the field.

How do we study the brain scientifically? Biopsychologists use both human and animal subjects, each with unique advantages. While humans have human brains (obviously!), animal subjects offer simpler systems to study, enable comparative approaches, and allow experimental manipulations that would be unethical with humans.

Experiments are the gold standard for determining causation. They use either between-subjects designs (different groups for each condition) or within-subjects designs (same group tested under different conditions). The key components include:

When experiments aren't possible, researchers use quasi-experimental studies that examine real-world exposure to conditions of interest, or case studies that provide in-depth examination of single subjects (though their generalizability is limited).

Biopsychology spans both pure research (knowledge for its own sake) and applied research (direct practical benefits), with translational research bridging the gap between discovery and application.

The field has four major divisions:

Remember This: Most significant discoveries in biopsychology come from "converging operations"—using multiple research approaches to compensate for the limitations of any single method.

Psychophysiology uses non-invasive techniques like electroencephalograms (EEG) to record brain activity from the body's surface. This approach has revealed interesting findings, like how people with schizophrenia have difficulty smoothly tracking moving objects.

Comparative Psychology takes a broader approach by comparing behaviors across species to understand evolution, genetics, and adaptive behaviors. This includes evolutionary psychology (examining behavior through its evolutionary origins) and behavioral genetics (studying genetic influences on behavior).

Biopsychologists rarely solve major problems with single experiments. Instead, they use converging operations—focusing different approaches on the same problem so the strengths of one method offset the weaknesses of others. For example, neuropsychology studies actual human patients but can't conduct controlled experiments, while physiological psychology can run controlled experiments but only on animals.

Critical thinking is essential when evaluating biopsychological claims. Consider the case of prefrontal lobotomy—a procedure once widely performed before its devastating consequences were fully understood. Scientists must use careful scientific inference, measuring observable events to logically infer unobservable ones.

The history of psychology features an ongoing battle between dichotomous thinking approaches:

Critical Insight: Dichotomous thinking has plagued psychology since its beginning. The brain-mind split from Descartes allowed science to study the physical brain while preserving the Church's domain over the human soul—a compromise that influenced thinking for centuries.

Is behavior inherited or learned? This nature-nurture debate has divided psychologists for generations. North American behaviorists like John B. Watson championed nurture (learning), while European ethologists studied instinctive behaviors, emphasizing nature (inheritance).

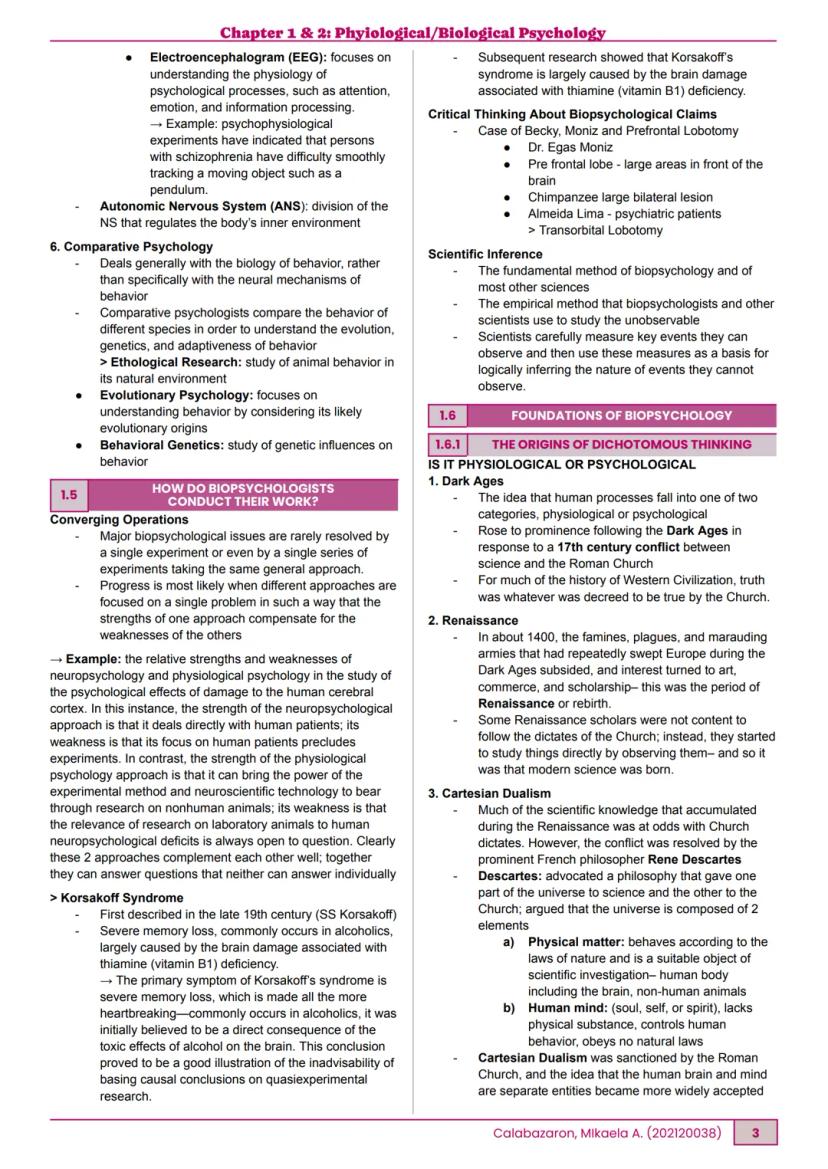

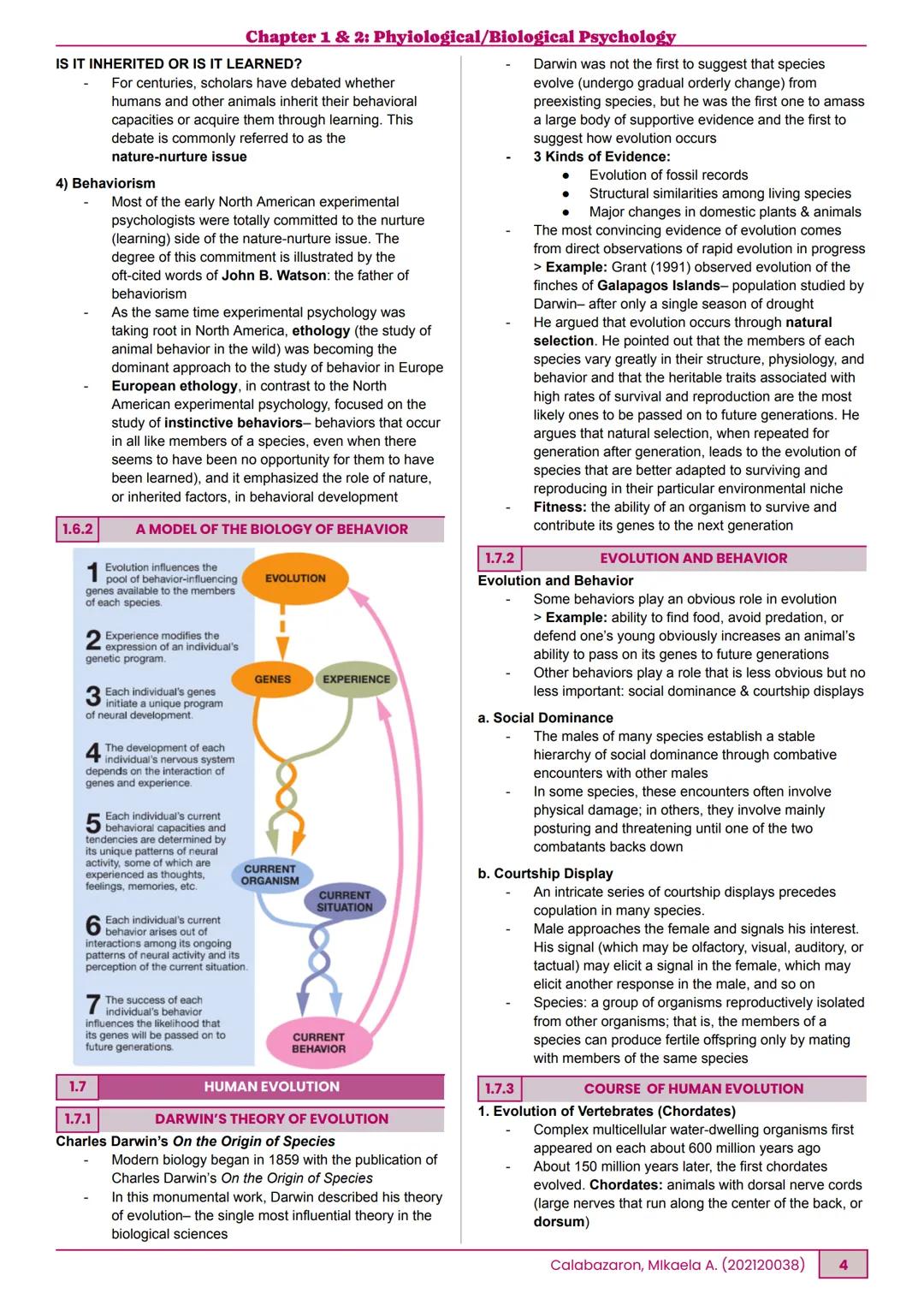

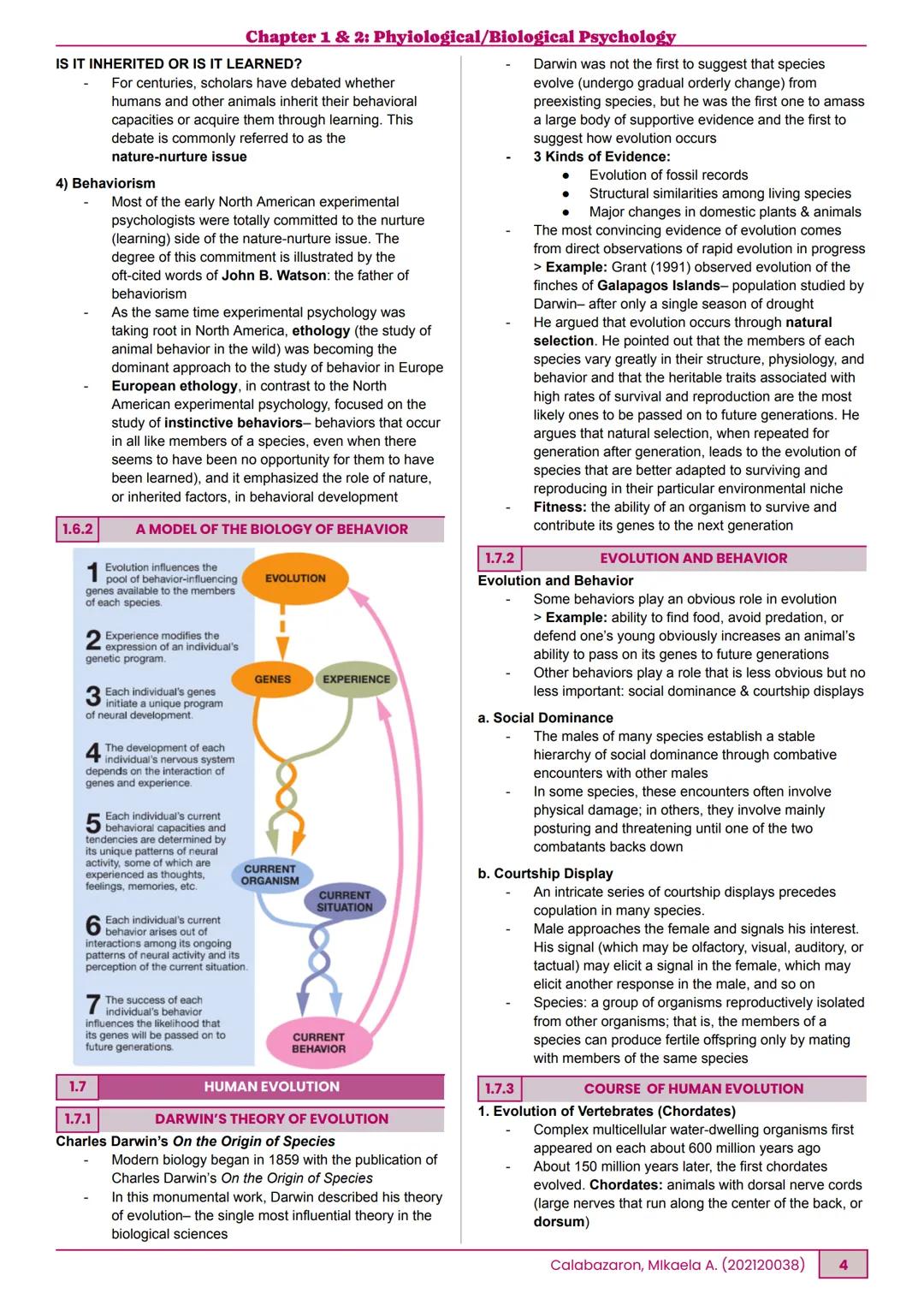

Modern biopsychology recognizes that behavior emerges from a complex interaction between evolution, genes, experience, neural development, and the current situation. This cyclical model shows how an individual's success influences whether their genes pass to future generations.

Charles Darwin's 1859 publication of On the Origin of Species revolutionized biology with his theory of evolution. Darwin wasn't the first to suggest species evolve, but he provided compelling evidence from fossil records, structural similarities among species, and changes in domestic plants and animals. His key insight was that evolution occurs through natural selection—heritable traits associated with survival and reproduction are passed to future generations.

Behaviors play crucial roles in evolution:

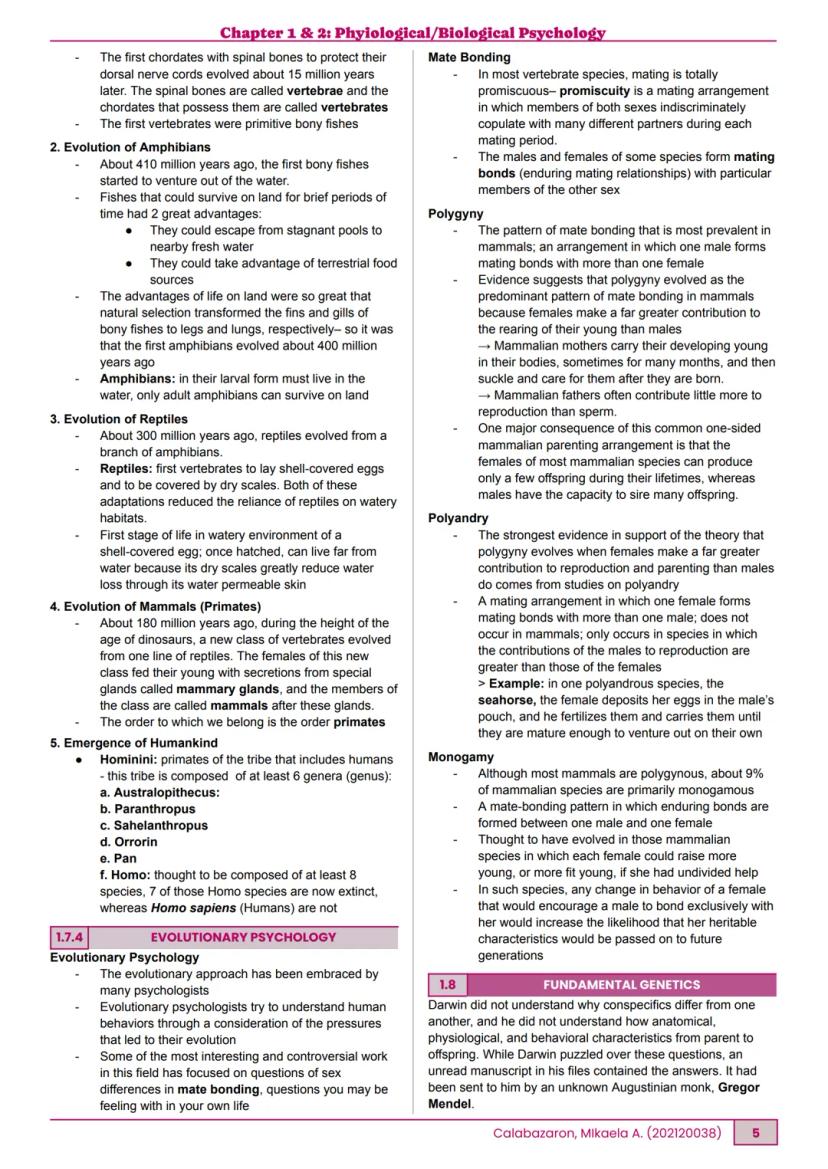

Human evolution followed a fascinating trajectory spanning hundreds of millions of years:

Fascinating Fact: Evolutionary psychologists study how different mating patterns evolved based on parental investment. In species where females contribute more to offspring care (like most mammals), polygyny (one male, multiple females) is common. In the rare cases where males contribute more, polyandry (one female, multiple males) can emerge—like in seahorses, where males carry the fertilized eggs!

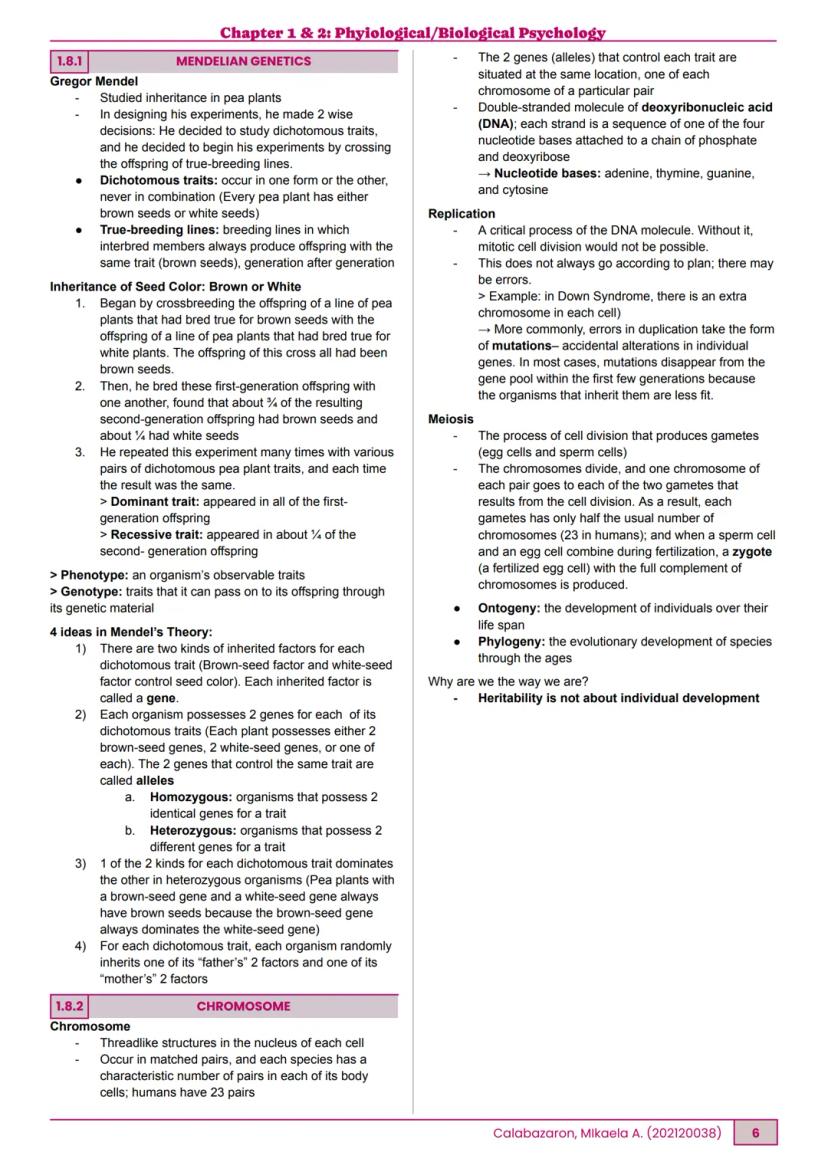

Gregor Mendel, an Augustinian monk, provided the answers to questions that puzzled even Darwin—how traits pass from parents to offspring. Studying pea plants, Mendel made two brilliant decisions: focusing on dichotomous traits and breeding from true-breeding lines (plants that consistently produced offspring with identical traits).

Mendel's groundbreaking experiments revealed fundamental principles of inheritance:

These principles explained why crossing brown-seed and white-seed plants produced all brown-seeded offspring in the first generation (F1), but approximately 3/4 brown and 1/4 white in the second generation (F2). The brown-seed gene was dominant while the white-seed gene was recessive.

Mendel's work revealed the difference between phenotype (observable traits) and genotype (genetic makeup). An organism can display a dominant trait while carrying a recessive gene that may appear in future generations.

His discoveries, initially overlooked by the scientific community, would eventually revolutionize our understanding of inheritance and provide the foundation for modern genetics. Darwin, ironically, had Mendel's manuscript in his files but never read it—missing the explanation to questions that troubled him throughout his life.

Key Insight: Mendel's work helps explain why family traits sometimes "skip" generations. A recessive trait (like white seeds) can remain hidden in heterozygous individuals for generations before appearing when two carriers have offspring.

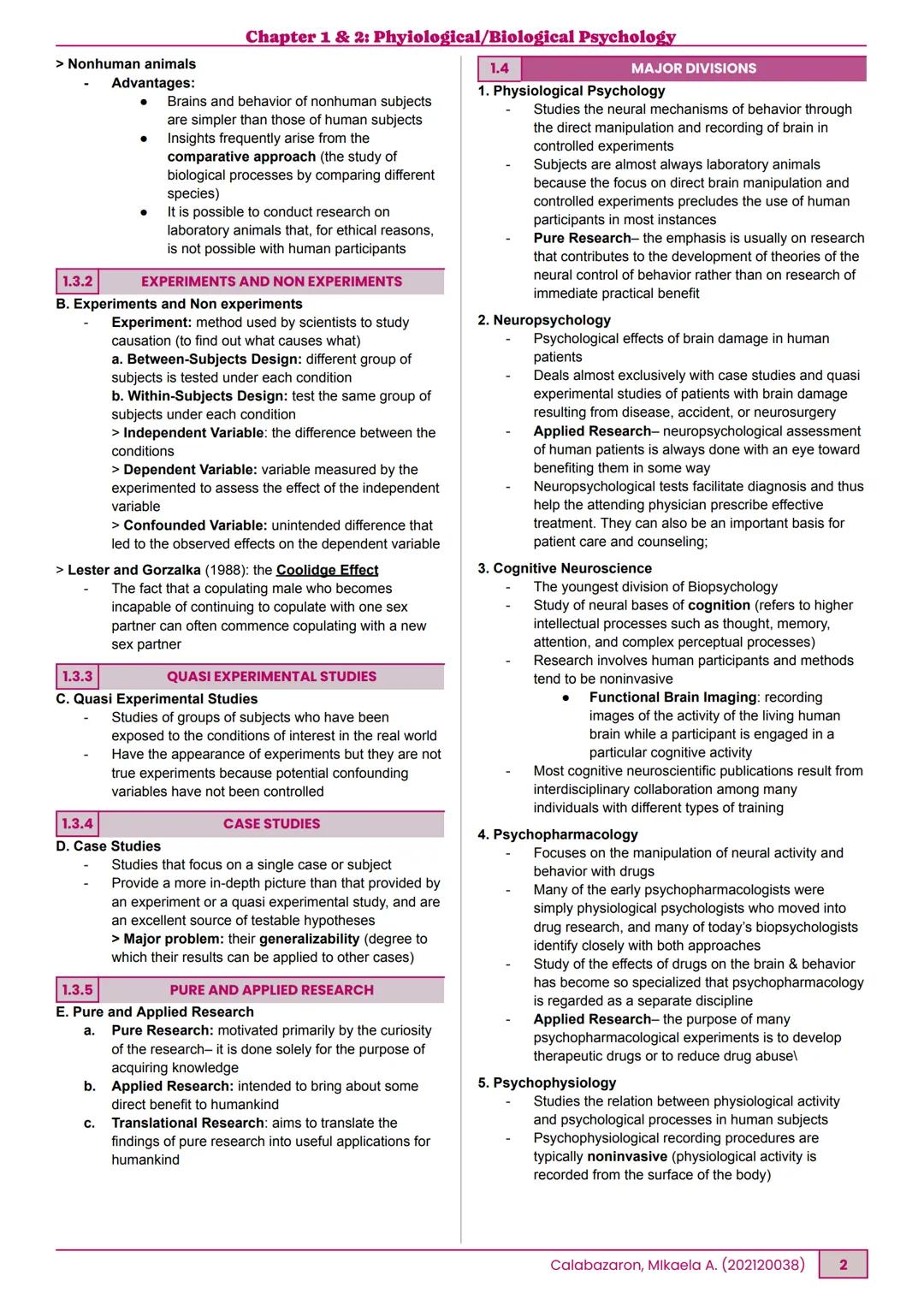

The physical basis of Mendel's inheritance theory is found in chromosomes—threadlike structures in cell nuclei that carry our genetic information. Humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes, with each pair containing matching genes (alleles) at the same locations.

Chromosomes are made of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), a double-stranded molecule composed of four nucleotide bases: adenine, thymine, guanine, and cytosine. The specific sequence of these bases forms the genetic code that determines our traits.

DNA replication is crucial for cell division but isn't always perfect. Errors can lead to conditions like Down Syndrome (an extra chromosome) or mutations (alterations in individual genes). Most mutations disappear from the gene pool within a few generations if they reduce an organism's fitness.

Meiosis is the specialized cell division process that produces gametes (egg and sperm cells). During meiosis, chromosome pairs separate, with one chromosome from each pair going to each new cell. This halves the chromosome number (to 23 in humans), which is restored to the full complement when sperm and egg unite during fertilization.

Two important developmental concepts are:

Understanding heritability is complex—it's not simply about individual development but about population patterns. Our traits result from complex interactions between our genetic inheritance and our environment, not just one or the other.

Remember: Heritability refers to population-level variation, not individual destiny. A highly heritable trait doesn't mean environment plays no role—it means genetic differences explain much of the variation seen across a population under specific environmental conditions.

Our AI companion is specifically built for the needs of students. Based on the millions of content pieces we have on the platform we can provide truly meaningful and relevant answers to students. But its not only about answers, the companion is even more about guiding students through their daily learning challenges, with personalised study plans, quizzes or content pieces in the chat and 100% personalisation based on the students skills and developments.

You can download the app in the Google Play Store and in the Apple App Store.

That's right! Enjoy free access to study content, connect with fellow students, and get instant help – all at your fingertips.

App Store

Google Play

The app is very easy to use and well designed. I have found everything I was looking for so far and have been able to learn a lot from the presentations! I will definitely use the app for a class assignment! And of course it also helps a lot as an inspiration.

Stefan S

iOS user

This app is really great. There are so many study notes and help [...]. My problem subject is French, for example, and the app has so many options for help. Thanks to this app, I have improved my French. I would recommend it to anyone.

Samantha Klich

Android user

Wow, I am really amazed. I just tried the app because I've seen it advertised many times and was absolutely stunned. This app is THE HELP you want for school and above all, it offers so many things, such as workouts and fact sheets, which have been VERY helpful to me personally.

Anna

iOS user

I think it’s very much worth it and you’ll end up using it a lot once you get the hang of it and even after looking at others notes you can still ask your Artificial intelligence buddy the question and ask to simplify it if you still don’t get it!!! In the end I think it’s worth it 😊👍 ⚠️Also DID I MENTION ITS FREEE YOU DON’T HAVE TO PAY FOR ANYTHING AND STILL GET YOUR GRADES IN PERFECTLY❗️❗️⚠️

Thomas R

iOS user

Knowunity is the BEST app I’ve used in a minute. This is not an ai review or anything this is genuinely coming from a 7th grade student (I know 2011 im young) but dude this app is a 10/10 i have maintained a 3.8 gpa and have plenty of time for gaming. I love it and my mom is just happy I got good grades

Brad T

Android user

Not only did it help me find the answer but it also showed me alternative ways to solve it. I was horrible in math and science but now I have an a in both subjects. Thanks for the help🤍🤍

David K

iOS user

The app's just great! All I have to do is enter the topic in the search bar and I get the response real fast. I don't have to watch 10 YouTube videos to understand something, so I'm saving my time. Highly recommended!

Sudenaz Ocak

Android user

In school I was really bad at maths but thanks to the app, I am doing better now. I am so grateful that you made the app.

Greenlight Bonnie

Android user

I found this app a couple years ago and it has only gotten better since then. I really love it because it can help with written questions and photo questions. Also, it can find study guides that other people have made as well as flashcard sets and practice tests. The free version is also amazing for students who might not be able to afford it. Would 100% recommend

Aubrey

iOS user

Best app if you're in Highschool or Junior high. I have been using this app for 2 school years and it's the best, it's good if you don't have anyone to help you with school work.😋🩷🎀

Marco B

iOS user

THE QUIZES AND FLASHCARDS ARE SO USEFUL AND I LOVE Knowunity AI. IT ALSO IS LITREALLY LIKE CHATGPT BUT SMARTER!! HELPED ME WITH MY MASCARA PROBLEMS TOO!! AS WELL AS MY REAL SUBJECTS ! DUHHH 😍😁😲🤑💗✨🎀😮

Elisha

iOS user

This app is phenomenal down to the correct info and the various topics you can study! I greatly recommend it for people who struggle with procrastination and those who need homework help. It has been perfectly accurate for world 1 history as far as I’ve seen! Geometry too!

Paul T

iOS user

The app is very easy to use and well designed. I have found everything I was looking for so far and have been able to learn a lot from the presentations! I will definitely use the app for a class assignment! And of course it also helps a lot as an inspiration.

Stefan S

iOS user

This app is really great. There are so many study notes and help [...]. My problem subject is French, for example, and the app has so many options for help. Thanks to this app, I have improved my French. I would recommend it to anyone.

Samantha Klich

Android user

Wow, I am really amazed. I just tried the app because I've seen it advertised many times and was absolutely stunned. This app is THE HELP you want for school and above all, it offers so many things, such as workouts and fact sheets, which have been VERY helpful to me personally.

Anna

iOS user

I think it’s very much worth it and you’ll end up using it a lot once you get the hang of it and even after looking at others notes you can still ask your Artificial intelligence buddy the question and ask to simplify it if you still don’t get it!!! In the end I think it’s worth it 😊👍 ⚠️Also DID I MENTION ITS FREEE YOU DON’T HAVE TO PAY FOR ANYTHING AND STILL GET YOUR GRADES IN PERFECTLY❗️❗️⚠️

Thomas R

iOS user

Knowunity is the BEST app I’ve used in a minute. This is not an ai review or anything this is genuinely coming from a 7th grade student (I know 2011 im young) but dude this app is a 10/10 i have maintained a 3.8 gpa and have plenty of time for gaming. I love it and my mom is just happy I got good grades

Brad T

Android user

Not only did it help me find the answer but it also showed me alternative ways to solve it. I was horrible in math and science but now I have an a in both subjects. Thanks for the help🤍🤍

David K

iOS user

The app's just great! All I have to do is enter the topic in the search bar and I get the response real fast. I don't have to watch 10 YouTube videos to understand something, so I'm saving my time. Highly recommended!

Sudenaz Ocak

Android user

In school I was really bad at maths but thanks to the app, I am doing better now. I am so grateful that you made the app.

Greenlight Bonnie

Android user

I found this app a couple years ago and it has only gotten better since then. I really love it because it can help with written questions and photo questions. Also, it can find study guides that other people have made as well as flashcard sets and practice tests. The free version is also amazing for students who might not be able to afford it. Would 100% recommend

Aubrey

iOS user

Best app if you're in Highschool or Junior high. I have been using this app for 2 school years and it's the best, it's good if you don't have anyone to help you with school work.😋🩷🎀

Marco B

iOS user

THE QUIZES AND FLASHCARDS ARE SO USEFUL AND I LOVE Knowunity AI. IT ALSO IS LITREALLY LIKE CHATGPT BUT SMARTER!! HELPED ME WITH MY MASCARA PROBLEMS TOO!! AS WELL AS MY REAL SUBJECTS ! DUHHH 😍😁😲🤑💗✨🎀😮

Elisha

iOS user

This app is phenomenal down to the correct info and the various topics you can study! I greatly recommend it for people who struggle with procrastination and those who need homework help. It has been perfectly accurate for world 1 history as far as I’ve seen! Geometry too!

Paul T

iOS user

eljiy

@eljiy_7gkrr

Physiological/Biological Psychology explores how our brain and biology influence our behavior and psychological processes. This field blends neuroscience with psychology to understand the biological mechanisms behind how we think, feel, and act. The following notes cover the foundations, research methods,... Show more

Access to all documents

Improve your grades

Join milions of students

Ever wonder what happens when your brain can't form new memories? The case of Jimmie G. demonstrates this heartbreaking reality. At 49 years old, Jimmie couldn't remember anything that happened since his early 20s due to Korsakoff Syndrome. Despite normal intelligence, he lived frozen in time—believing he was 19 and unable to form new memories, even forgetting conversations moments after having them.

Biopsychology is the scientific study of the biology of behavior. Unlike early thinkers like Aristotle (who believed the heart was central to thought), modern biopsychology follows the tradition of Hippocrates and Plato, who correctly identified the brain as the command center for behavior and thought. A key historical figure, Donald Olding Hebb, established biopsychology as a separate discipline in the 20th century with his 1949 work "The Organization of Behaviour."

Biopsychology integrates knowledge from multiple neuroscience disciplines including:

Insight Box: Biopsychologists use an "eclectic approach" combining experiments with humans and lab animals, clinical case studies, and logical arguments based on observations of daily life—a signature characteristic of the field.

Access to all documents

Improve your grades

Join milions of students

How do we study the brain scientifically? Biopsychologists use both human and animal subjects, each with unique advantages. While humans have human brains (obviously!), animal subjects offer simpler systems to study, enable comparative approaches, and allow experimental manipulations that would be unethical with humans.

Experiments are the gold standard for determining causation. They use either between-subjects designs (different groups for each condition) or within-subjects designs (same group tested under different conditions). The key components include:

When experiments aren't possible, researchers use quasi-experimental studies that examine real-world exposure to conditions of interest, or case studies that provide in-depth examination of single subjects (though their generalizability is limited).

Biopsychology spans both pure research (knowledge for its own sake) and applied research (direct practical benefits), with translational research bridging the gap between discovery and application.

The field has four major divisions:

Remember This: Most significant discoveries in biopsychology come from "converging operations"—using multiple research approaches to compensate for the limitations of any single method.

Access to all documents

Improve your grades

Join milions of students

Psychophysiology uses non-invasive techniques like electroencephalograms (EEG) to record brain activity from the body's surface. This approach has revealed interesting findings, like how people with schizophrenia have difficulty smoothly tracking moving objects.

Comparative Psychology takes a broader approach by comparing behaviors across species to understand evolution, genetics, and adaptive behaviors. This includes evolutionary psychology (examining behavior through its evolutionary origins) and behavioral genetics (studying genetic influences on behavior).

Biopsychologists rarely solve major problems with single experiments. Instead, they use converging operations—focusing different approaches on the same problem so the strengths of one method offset the weaknesses of others. For example, neuropsychology studies actual human patients but can't conduct controlled experiments, while physiological psychology can run controlled experiments but only on animals.

Critical thinking is essential when evaluating biopsychological claims. Consider the case of prefrontal lobotomy—a procedure once widely performed before its devastating consequences were fully understood. Scientists must use careful scientific inference, measuring observable events to logically infer unobservable ones.

The history of psychology features an ongoing battle between dichotomous thinking approaches:

Critical Insight: Dichotomous thinking has plagued psychology since its beginning. The brain-mind split from Descartes allowed science to study the physical brain while preserving the Church's domain over the human soul—a compromise that influenced thinking for centuries.

Access to all documents

Improve your grades

Join milions of students

Is behavior inherited or learned? This nature-nurture debate has divided psychologists for generations. North American behaviorists like John B. Watson championed nurture (learning), while European ethologists studied instinctive behaviors, emphasizing nature (inheritance).

Modern biopsychology recognizes that behavior emerges from a complex interaction between evolution, genes, experience, neural development, and the current situation. This cyclical model shows how an individual's success influences whether their genes pass to future generations.

Charles Darwin's 1859 publication of On the Origin of Species revolutionized biology with his theory of evolution. Darwin wasn't the first to suggest species evolve, but he provided compelling evidence from fossil records, structural similarities among species, and changes in domestic plants and animals. His key insight was that evolution occurs through natural selection—heritable traits associated with survival and reproduction are passed to future generations.

Behaviors play crucial roles in evolution:

Human evolution followed a fascinating trajectory spanning hundreds of millions of years:

Fascinating Fact: Evolutionary psychologists study how different mating patterns evolved based on parental investment. In species where females contribute more to offspring care (like most mammals), polygyny (one male, multiple females) is common. In the rare cases where males contribute more, polyandry (one female, multiple males) can emerge—like in seahorses, where males carry the fertilized eggs!

Access to all documents

Improve your grades

Join milions of students

Gregor Mendel, an Augustinian monk, provided the answers to questions that puzzled even Darwin—how traits pass from parents to offspring. Studying pea plants, Mendel made two brilliant decisions: focusing on dichotomous traits and breeding from true-breeding lines (plants that consistently produced offspring with identical traits).

Mendel's groundbreaking experiments revealed fundamental principles of inheritance:

These principles explained why crossing brown-seed and white-seed plants produced all brown-seeded offspring in the first generation (F1), but approximately 3/4 brown and 1/4 white in the second generation (F2). The brown-seed gene was dominant while the white-seed gene was recessive.

Mendel's work revealed the difference between phenotype (observable traits) and genotype (genetic makeup). An organism can display a dominant trait while carrying a recessive gene that may appear in future generations.

His discoveries, initially overlooked by the scientific community, would eventually revolutionize our understanding of inheritance and provide the foundation for modern genetics. Darwin, ironically, had Mendel's manuscript in his files but never read it—missing the explanation to questions that troubled him throughout his life.

Key Insight: Mendel's work helps explain why family traits sometimes "skip" generations. A recessive trait (like white seeds) can remain hidden in heterozygous individuals for generations before appearing when two carriers have offspring.

Access to all documents

Improve your grades

Join milions of students

The physical basis of Mendel's inheritance theory is found in chromosomes—threadlike structures in cell nuclei that carry our genetic information. Humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes, with each pair containing matching genes (alleles) at the same locations.

Chromosomes are made of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), a double-stranded molecule composed of four nucleotide bases: adenine, thymine, guanine, and cytosine. The specific sequence of these bases forms the genetic code that determines our traits.

DNA replication is crucial for cell division but isn't always perfect. Errors can lead to conditions like Down Syndrome (an extra chromosome) or mutations (alterations in individual genes). Most mutations disappear from the gene pool within a few generations if they reduce an organism's fitness.

Meiosis is the specialized cell division process that produces gametes (egg and sperm cells). During meiosis, chromosome pairs separate, with one chromosome from each pair going to each new cell. This halves the chromosome number (to 23 in humans), which is restored to the full complement when sperm and egg unite during fertilization.

Two important developmental concepts are:

Understanding heritability is complex—it's not simply about individual development but about population patterns. Our traits result from complex interactions between our genetic inheritance and our environment, not just one or the other.

Remember: Heritability refers to population-level variation, not individual destiny. A highly heritable trait doesn't mean environment plays no role—it means genetic differences explain much of the variation seen across a population under specific environmental conditions.

Our AI companion is specifically built for the needs of students. Based on the millions of content pieces we have on the platform we can provide truly meaningful and relevant answers to students. But its not only about answers, the companion is even more about guiding students through their daily learning challenges, with personalised study plans, quizzes or content pieces in the chat and 100% personalisation based on the students skills and developments.

You can download the app in the Google Play Store and in the Apple App Store.

That's right! Enjoy free access to study content, connect with fellow students, and get instant help – all at your fingertips.

2

Smart Tools NEW

Transform this note into: ✓ 50+ Practice Questions ✓ Interactive Flashcards ✓ Full Practice Test ✓ Essay Outlines

App Store

Google Play

The app is very easy to use and well designed. I have found everything I was looking for so far and have been able to learn a lot from the presentations! I will definitely use the app for a class assignment! And of course it also helps a lot as an inspiration.

Stefan S

iOS user

This app is really great. There are so many study notes and help [...]. My problem subject is French, for example, and the app has so many options for help. Thanks to this app, I have improved my French. I would recommend it to anyone.

Samantha Klich

Android user

Wow, I am really amazed. I just tried the app because I've seen it advertised many times and was absolutely stunned. This app is THE HELP you want for school and above all, it offers so many things, such as workouts and fact sheets, which have been VERY helpful to me personally.

Anna

iOS user

I think it’s very much worth it and you’ll end up using it a lot once you get the hang of it and even after looking at others notes you can still ask your Artificial intelligence buddy the question and ask to simplify it if you still don’t get it!!! In the end I think it’s worth it 😊👍 ⚠️Also DID I MENTION ITS FREEE YOU DON’T HAVE TO PAY FOR ANYTHING AND STILL GET YOUR GRADES IN PERFECTLY❗️❗️⚠️

Thomas R

iOS user

Knowunity is the BEST app I’ve used in a minute. This is not an ai review or anything this is genuinely coming from a 7th grade student (I know 2011 im young) but dude this app is a 10/10 i have maintained a 3.8 gpa and have plenty of time for gaming. I love it and my mom is just happy I got good grades

Brad T

Android user

Not only did it help me find the answer but it also showed me alternative ways to solve it. I was horrible in math and science but now I have an a in both subjects. Thanks for the help🤍🤍

David K

iOS user

The app's just great! All I have to do is enter the topic in the search bar and I get the response real fast. I don't have to watch 10 YouTube videos to understand something, so I'm saving my time. Highly recommended!

Sudenaz Ocak

Android user

In school I was really bad at maths but thanks to the app, I am doing better now. I am so grateful that you made the app.

Greenlight Bonnie

Android user

I found this app a couple years ago and it has only gotten better since then. I really love it because it can help with written questions and photo questions. Also, it can find study guides that other people have made as well as flashcard sets and practice tests. The free version is also amazing for students who might not be able to afford it. Would 100% recommend

Aubrey

iOS user

Best app if you're in Highschool or Junior high. I have been using this app for 2 school years and it's the best, it's good if you don't have anyone to help you with school work.😋🩷🎀

Marco B

iOS user

THE QUIZES AND FLASHCARDS ARE SO USEFUL AND I LOVE Knowunity AI. IT ALSO IS LITREALLY LIKE CHATGPT BUT SMARTER!! HELPED ME WITH MY MASCARA PROBLEMS TOO!! AS WELL AS MY REAL SUBJECTS ! DUHHH 😍😁😲🤑💗✨🎀😮

Elisha

iOS user

This app is phenomenal down to the correct info and the various topics you can study! I greatly recommend it for people who struggle with procrastination and those who need homework help. It has been perfectly accurate for world 1 history as far as I’ve seen! Geometry too!

Paul T

iOS user

The app is very easy to use and well designed. I have found everything I was looking for so far and have been able to learn a lot from the presentations! I will definitely use the app for a class assignment! And of course it also helps a lot as an inspiration.

Stefan S

iOS user

This app is really great. There are so many study notes and help [...]. My problem subject is French, for example, and the app has so many options for help. Thanks to this app, I have improved my French. I would recommend it to anyone.

Samantha Klich

Android user

Wow, I am really amazed. I just tried the app because I've seen it advertised many times and was absolutely stunned. This app is THE HELP you want for school and above all, it offers so many things, such as workouts and fact sheets, which have been VERY helpful to me personally.

Anna

iOS user

I think it’s very much worth it and you’ll end up using it a lot once you get the hang of it and even after looking at others notes you can still ask your Artificial intelligence buddy the question and ask to simplify it if you still don’t get it!!! In the end I think it’s worth it 😊👍 ⚠️Also DID I MENTION ITS FREEE YOU DON’T HAVE TO PAY FOR ANYTHING AND STILL GET YOUR GRADES IN PERFECTLY❗️❗️⚠️

Thomas R

iOS user

Knowunity is the BEST app I’ve used in a minute. This is not an ai review or anything this is genuinely coming from a 7th grade student (I know 2011 im young) but dude this app is a 10/10 i have maintained a 3.8 gpa and have plenty of time for gaming. I love it and my mom is just happy I got good grades

Brad T

Android user

Not only did it help me find the answer but it also showed me alternative ways to solve it. I was horrible in math and science but now I have an a in both subjects. Thanks for the help🤍🤍

David K

iOS user

The app's just great! All I have to do is enter the topic in the search bar and I get the response real fast. I don't have to watch 10 YouTube videos to understand something, so I'm saving my time. Highly recommended!

Sudenaz Ocak

Android user

In school I was really bad at maths but thanks to the app, I am doing better now. I am so grateful that you made the app.

Greenlight Bonnie

Android user

I found this app a couple years ago and it has only gotten better since then. I really love it because it can help with written questions and photo questions. Also, it can find study guides that other people have made as well as flashcard sets and practice tests. The free version is also amazing for students who might not be able to afford it. Would 100% recommend

Aubrey

iOS user

Best app if you're in Highschool or Junior high. I have been using this app for 2 school years and it's the best, it's good if you don't have anyone to help you with school work.😋🩷🎀

Marco B

iOS user

THE QUIZES AND FLASHCARDS ARE SO USEFUL AND I LOVE Knowunity AI. IT ALSO IS LITREALLY LIKE CHATGPT BUT SMARTER!! HELPED ME WITH MY MASCARA PROBLEMS TOO!! AS WELL AS MY REAL SUBJECTS ! DUHHH 😍😁😲🤑💗✨🎀😮

Elisha

iOS user

This app is phenomenal down to the correct info and the various topics you can study! I greatly recommend it for people who struggle with procrastination and those who need homework help. It has been perfectly accurate for world 1 history as far as I’ve seen! Geometry too!

Paul T

iOS user